Longtermism and politics: towards a longtermist utopia?

Tyler John and William MacAskill have written a book chapter on how political institutions might reform themselves to care more about the long-term future.

Political science tells us that the practices of most governments are at stark odds with longtermism. This may seem obvious. After all, governments are run by and for presently existing people; future generations have essentially no political representation, and even in the face of the catastrophic risk to future generations posed by climate change, governments the world over have failed to effectively respond. But the problems of political short-termism are even more substantial than they appear. Elected officials usually operate on 2-5 year time horizons, failing to look ahead even into the problems of the next decade. Estimates of the financial impacts of legislation typically extend to just a few years to a decade, and politicians are rarely able to allocate time to agendas which do not bear fruit until after the next election. In addition to the ordinary causes of human short-termism, which are substantial, politics brings unique challenges of coordination, polarization, short-term institutional incentives, and more.

Despite the relatively grim picture of political time horizons offered by political science, the problems of political short-termism are neither necessary nor inevitable. In principle, the State could serve as a powerful tool for positively shaping the long-term future. Governments collectively spend over $25 trillion per year, and they are our best means of solving large-scale coordination problems. Moreover, research in legal theory and the social sciences shows us that countries’ laws and policies have a profound effect on the moral norms and attitudes that people see as acceptable. The problem of aligning government incentives with the interests of future generations should therefore be a moral priority.

Tyler John also presented a version of this same idea as a talk at EA Global earlier this year; you can view the slides and transcript here.

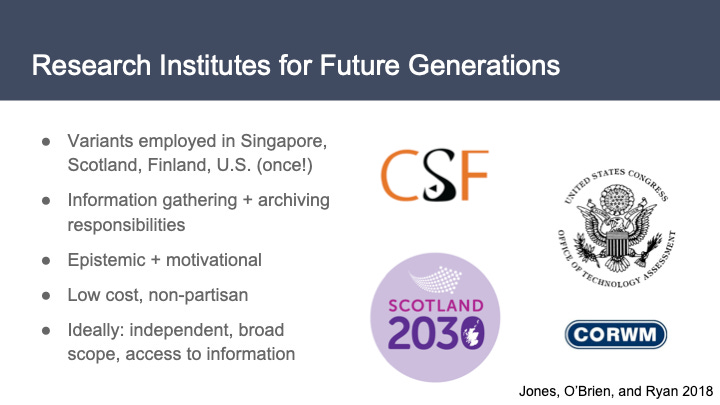

After restating the case for longtermism, the authors suggest a number of proposals to address the deficit of longtermist thinking across the political system. These include more research produced by governments on long-term trends, “futures assemblies” to enable direct representation of the interest of future generations, and “posterity impact statements” which sound quite a bit like the kind of policy impact assessments that already happen (at least in e.g. UK government) but over a much longer timescale than most policy programmes: think decades instead of years.

While posterity impact assessments (PIAs) are a much newer idea, they are not entirely without precedent. The UK’s 2020 Well-being of Future Generations Bill, started in the House of Lords by Lord John Bird, requires all public bodies to “(a) publish an assessment (“future generations impact assessment“) of the likely impact of the proposal on its well-being objectives, or (b) publish a statement setting out its reasons for concluding that it does not need to carry out a future generations impact assessment” upon proposing any change in public expenditure or policy. The impact statements must assess the impact of policy on “all future generations... at least 25 years from the date” of publication, and include a statement of how any adverse impacts will be mitigated.

A further, more radical suggestion follows these three, which is to create a legislative house for future generations. I would agree with the authors that we should distinguish between political proposals with varying amounts of ‘shovel-readiness’, and given that longtermism is still in its very earliest stages of acceptance into the political discourse perhaps starting with proposing small changes is a good idea.

In the system we envision, bicameral national legislatures would be constituted by a lower house focused on attending to the interests of the people who exist today and an upper house focused on attending to the interests of all future generations. Legislation may be proposed in either house, but must be passed by both houses to become law. Thus, each house would provide a check on the other, ensuring that neither future-oriented nor present-focused legislation can be dominant. A strong constitution providing basic rights and freedoms to both presently-existing and future people would provide another strong backstop against the tyranny of either house.

There is extended discussion of the kinds of incentives that would face such a House, and some of the pros and cons are discussed.

While the reforms proposed are significant, and will help to put society on a better long-term trajectory, we see this discussion as being merely a first step on a long path toward truly longtermist political institutions. The movement for longtermist political reform will require substantial advocacy, but it will also require substantially more research. Other promising possibilities which require further research include longer election cycles to reduce perverse election incentives, novel commitment mechanisms to enable longer-term decision-making, extra votes for parents to use on behalf of their children (or “Demeny voting”), taxation for long-run negative and positive externalities, and broader long-term pay-for-performance incentive schemes such as tying public pensions to national performance. Because the literature on political short-termism is young and still relatively conservative, there are likely to be many more promising possibilities that we have not yet uncovered.

Overall I think it’s a useful paper that’s fun to read, but have no idea if such ideas are within the typical government official’s Overton window. I appreciate the attempt to engage with practical features of real-world political systems but would like to see an assessment of these ideas by someone with less of a philosophy background and more of an insider policy background.

Until then, it’s certainly fun to imagine!